Illustrations as visual texts in 19th-Century costumbrismo collections

Mary L. Coffey, Pomona College

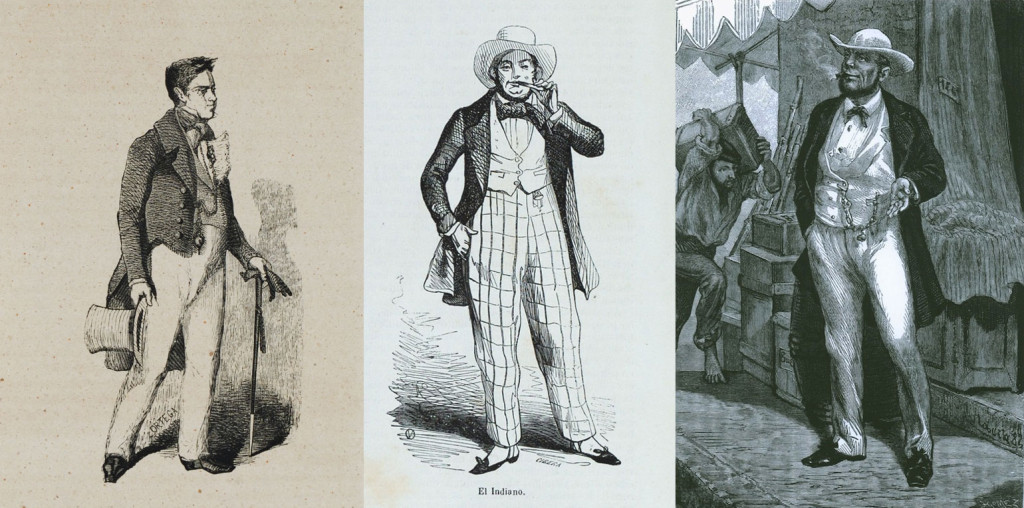

“El indiano”

These illustrations of the costumbrista tipo “El indiano” are, from left to right, from Los españoles pintados por por sí mismos in the original edition from 1843-44, the collection’s reprint from 1851 and from the later collection, Los españoles, americanos y lusitanos pintados por sí mismos published in 1881. The illustrations provide evidence of the growing anxiety about the economic power of the Americas and its effect on the metropolis.

The first image shows a somewhat diffident young man, hat in hand, returning to his country of origin. He looks off to the side, unknowingly presenting himself for our appraisal of his new clothing and the trappings of his new-found wealth. In the middle image, from 1851, the “indiano” is no longer unaware and instead manifests a direct challenge to us as viewers. Completely aware of the power of his wealth and the effect of his fashion, he boldly returns the gaze, hat pushed back on his head, one hand on his pocket and a cigar in the other, as reference to the colonial economy of tobacco. These stereotypical components of the “indiano” are repeated in the third and final image from 1881. In this portrait we again see the indiano with one hand in his pocket and the other holding a cigar. Yet he no longer needs to look the spectator in the eye, in part because his wealth is now such that we are reduced to the status of the second man depicted in the illustration, a barefoot Spaniard hired to unload the rich man’s trunks onto the docks. This indiano signals his financial power through the ostentatious show of his watchchain, through his self-satisfied smile and through the cut and polish of his clothing and shoes. Even more telling is the contrast between the light colored clothing of the tropics and the sun-burnished skin of the indiano, who returns to Spain not exactly as a Spaniard but more as a colonial other whose skin color is darker than that of the dockworker, despite the fact that he stands in the light and the Spaniard remains in the shadows.

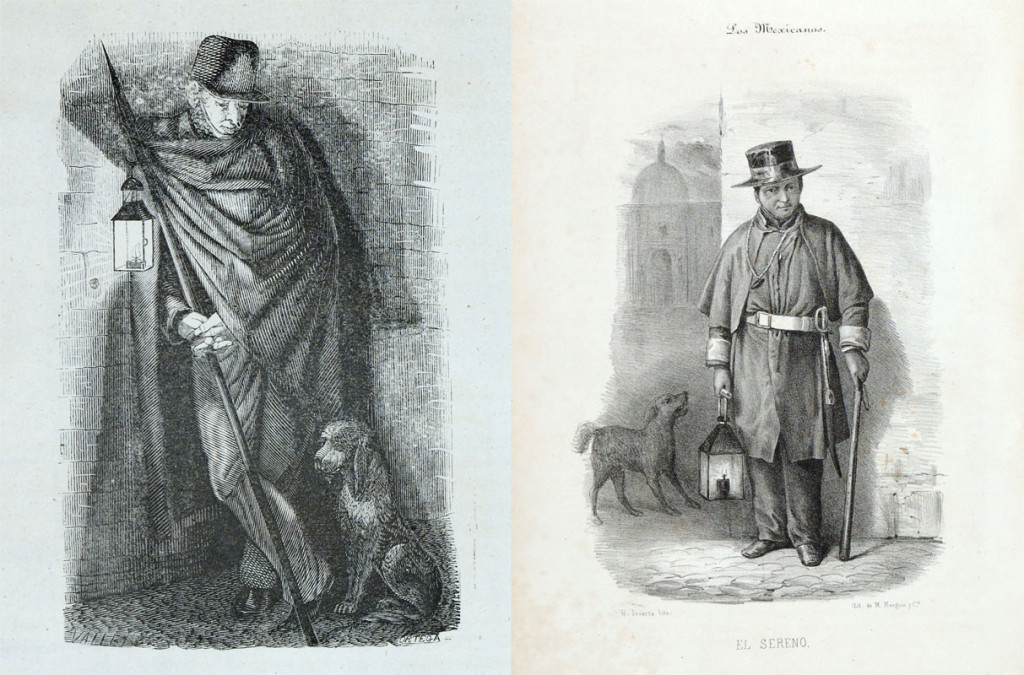

“El sereno”

In this pair of images we see “El sereno” from Los españoles pintados por sí mismos (1843-44) on the left and its counterpart from the 1854 Mexican collection, Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos. Certainly these images reflect certain cultural traditions associated with the social role of the nightwatchman, but the similarities between these two images (i.e., staff, dog, lantern, hat and muffler) are striking. While the titles of the two collections might lead one to expect portraits of national singularity, these two examples make manifestly clear that what is at stake is not cultural difference but similarity. Both Spain and Mexico, as these collections go to some length to show, are sovereign nations with the right to claim political independence.

“La maja” and “La china”

In this pair of images, again from the 1843-44 collection on the left and the 1854 collection on the right, we see representations of the Spanish “La maja” and her Mexican counterpart “La china.” Both terms refer to young, attractive women of generally humble origins who evidence an awareness of fashion. Again there are striking similarities between the images, in the physical stance of each woman (with one elbow bent to place the hand on the waist, and the head turned slightly to the side with the chin raised), the attention to their fringed shawls, necklaces, and fashionable skirts, which are short enough to show off their feet and provide a tantalizing glimpse of their ankles. Distinct from the images of the coqueta, “La maja” and “La china” represent images of feminine attractiveness that place a premium on youth and urbanity. Again, the similarities here only prove to underscore that Mexico shares the cultural fullness of its former metropolis and, in the expanded detail of the image, may be seen to have actually outdone its former colonial master in terms of aesthetic sensibility and personality.

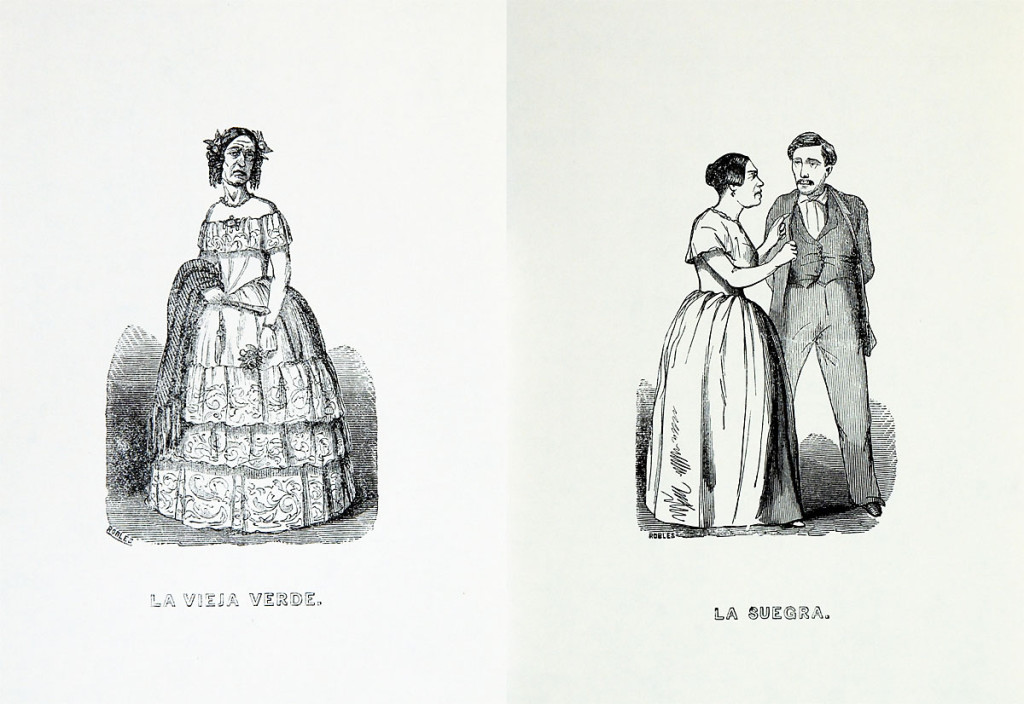

“La vieja verde” and “La suegra”

In striking contrast to the Spanish and Mexican illustrations of the fashionable young woman, the collection Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos (1852) presents these two riveting images of older women, both of whom are not only unattractive but also clearly unpleasant. On the left is “La vieja verde,” an image of an spinster tricked out in the latest fashion with a stylish hairdo usually reserved for younger women. A rarely seen feminine version of the “viejo verde” (or “dirty old man”), this image signals a social type with an unpleasant personality formed by a series of disappointments in life. The woman’s gaze is notably directed to us as viewers, placing us squarely in the position of an object of her interest. On the left is “La suegra,” a similarly ugly representation of another feminine type who makes life difficult for men. In this illustration the man himself is depicted as the long-suffering and brow-beaten victim of her frequent tirades.

No other Spanish or Latin American collection contains similar types, and indeed in the Cuban collection there are no counterparts to “La maja,” or “La china.” Indeed, the other illustrations for female types in the Cuban collections are also of profoundly unattractive older women. This unique representation of women in Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos raises important questions with respect to the intersection of gender and empire and the articulation of a Cuban national identity. I would argue that these illustrations represent a complex rearticulation of the concept of “la madre-patria.” “La vieja verde” can be read as an image of the “madre-patria” that seeks to parasitically extract the economic vitality, youth and virility of the Cuban economy, while “La suegra” serves to illustrate the attempt of “la madre-patria: to beat Cuban masculinity into submission. In short, these illustrations, and the texts that accompany them, serve as a powerful yet partially masked critique of colonial relations even as they underscore a presentation of Cuban masculinity that attempts to upend traditional gendered notions of empire.