My research is predominantly organized around numerical modeling of subsurface volcanic processes. I would never claim to be a field geologist, but even so my insight into volcanic processes is enhanced every time I have a chance to observe volcanic phenomena and products directly. Happily, this past year I have enjoyed ample opportunities to visit several different volcanoes–on my own, with colleagues, and with students.

Morro Rock, CA (Mar., 2017): During a trip up the California coast I visited Morro Rock. The iconic 575′ volcanic plug is the westernmost of an aligned series of intrusives that formed ~22 million years ago. Originally located deep underground, this dacitic plug is probably the remains of a volcanic conduit system. Today it anchors the Morro Bay harbor, and is a stunning landmark along this stretch of the California coast.

Morro Rock dacitic plug at sunset

Kilauea/Mauna Loa/Hualalei, HI (May, 2017): Before and after the Cordilleran GSA meeting in Honolulu I had a chance to spend a number of days on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Several of these days were spent on a GSA field trip run by Dr. Tina Neal and Dr. Don Swanson, current and former Scientists in Charge at the Hawaii Volcano Observatory. On this engaging and informative trip we were introduced to a number of stunning volcanic landscapes and processes–one of my favorites was a superelevated lava flow emplaced in 1974–but our primary focus was to examine several summit deposits and processes on Kilauea, including those associated with the infamous 1790 explosive sequence.

Super elevated flow channel (banked flow seen at left) with gas from Overlook Crater, Kilauea caldera, in the background

After GSA, where I presented an analysis of caldera formation on Mars, I returned to the Big Island for some less formal exploration, generously guided by my friend and Emeritus Professor of Geology (retired) Rick Hazlett, who now lives in Hilo. One of my dreams for the Volcanology course I teach at Pomona is to secure enough funding to support an every-other-year trip to Hawaii for the enrolled students; this would enable them to apply their quantitative skills to field-based problems in this volcanic wonderland, and would also enrich the course with several key qualitative analyses. With that goal in mind, Rick and I explored an array of sites on Kilauea, Mauna Loa and Hualalei to assess their suitability. We walked through lava tubes, looked at channelized flow processes and tree molds, enjoyed coastal exposures, did a detailed walk-through of Kilauea Iki, and visited a large number of lava-structure interactions to gain insight into this pervasive element of the Hawaiian experience.

Mantle xenoliths in a flow on the Big Island

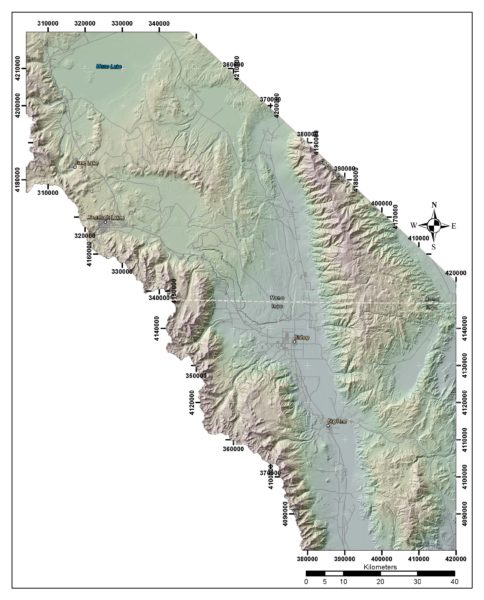

Mt. Hood, OR (Aug., 2017): Toward the end of the summer I attended the IAVCEI Scientific Conference in Portland, where I presented a “where are we now” talk sharing new insights into the mechanics of radial dike formation at several different scales. One day of the conference was dedicated to field trips, and I had the good fortune to see a volcano I’d never visited: the iconic Mt. Hood. The lovely composite cone geometry is a product of lava effusions and repeated lava dome collapses that fed pyroclastic flows, and it has experienced vigorous lahar activity as well.

Lamar deposits from Mt Hood, OR

Mt. St. Helens, WA (Aug., 2017): After the IAVCEI conference my family flew up to Oregon to watch the solar eclipse (the zone of totality passed just south of Portland; it was incredible!), and we took the opportunity to visit Mt. St. Helens. This trip was a “tourist” visit, not a professional one per se, but I took a lot of photos to use in my volcanology course and really enjoyed the chance to see the products of the volcanic avalanche (I visited the much larger deposits around Mt. Shasta in California a few years back), the current dome growing in the crater, and the trees that had been knocked flat by the blast. Roughly a third of a century later the region has recovered to some extent, but the signature of the May 1981 eruption still dominates the landscape quite clearly.

Mt St Helens volcano, WA

Amboy Crater, CA (Feb., 2018): After studying lava flows for a bit, my volcanology class took a trip out to see the Amboy Crater scoria cone in the Mojave Desert. I have been visiting this site for many years, but see something new every time I’m there. This year, in addition to studying the sequence of events that formed the cone and surrounding lava flows, we took some first-order measurements of tumuli to try and assess the magma pressure responsible for their inflation. It’s nice having such a pristine volcano only a few hours away from campus!

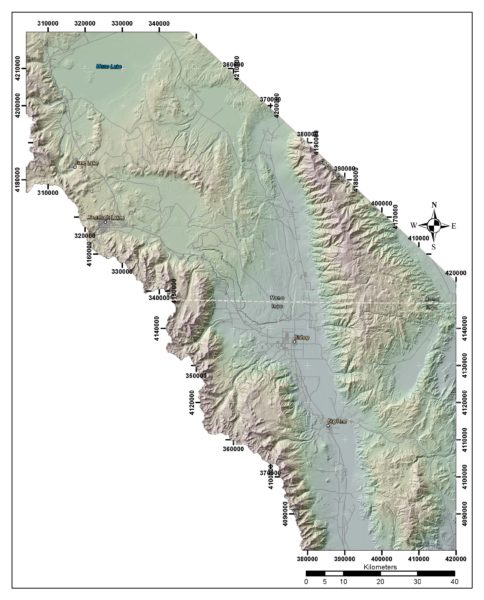

BPVF/Long Valley/Panum Crater, CA (Apr., 2018): Toward the end of the spring semester the volcanology and petrology classes took a joint, multi-day field trip to see parts of Owen’s Valley, Long Valley and the Mono Basin, which together exhibit a breathtaking array of volcanic styles.

Owens Valley, Long Valley and Mono Basin field area.

Several of our stops occurred in the Big Pine Volcanic Field (BPVF), where we examined S-type granites and Independence dikes at Kern Knob, the faulted Fish Springs cone, and the incredible Papoose Canyon cone which has been neatly bisected by a fluvial channel, thereby providing hands-on access to the majority of the xenolith-rich flow sequence that built the cone.

Entrance to Papoose Canyon.

Papoose Canyon xenolith and contact.

At Long Valley we spent considerable time studying deposits emplaced during the cataclysmic caldera-forming Bishop Tuff eruption that occurred 767 thousand years ago. This ‘supereruption’ emplaced ~600 km^3 of felsic material over a few short days as the ring faults ‘unzipped.’ Much of our time was spent examining the airfall and ignimbrite exposures at the classic Chalfant quarry site, but we also visited several other locales to examine variations in the degree of ignimbrite welding and to view the southern part of the caldera and resurgent dome from afar!

Bishop Tuff airfall and ignimbrite, Chalfant Quarry

Finally, not content with basaltic cones and massive ignimbrite eruption deposits, we visited Panum Crater, the northernmost member of the Mono Domes and, having formed only 600 yrs ago, the youngest. Although it has enjoyed a complex history, Panum today is defined by a cavity formed during an early phreatomagmatic explosion, a low tuff ring formed during an intermediate Strombolian eruption, and a terminal, conduit-plugging silicic dome that exhibits obsidian banding, bread crust textures, and debris from collapsed spines. Yielding stunning views across the Sierran front and the Mono Basin (including the Paoha, Negit and Black Point constructs — parts of the volcanic story that will have to wait for a different trip!), Panum was a great way to end the middle day of our field trip!

Lovely fracturing in obsidian atop Panum Crater’s silicic dome

Mono Lake (left), Mono Domes (right skyline), Panum crater tuff ring (foreground, curving to the right) and silicic dome (casting shadow)

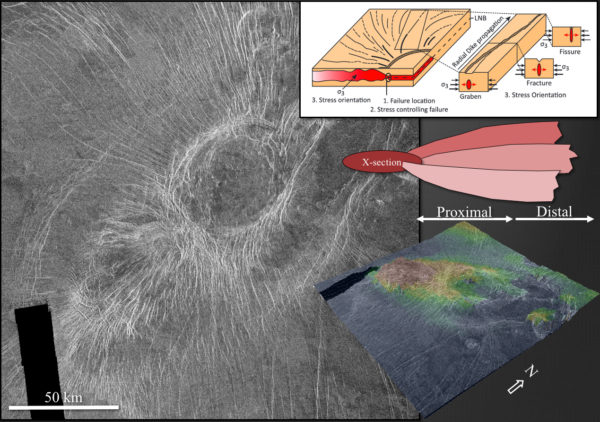

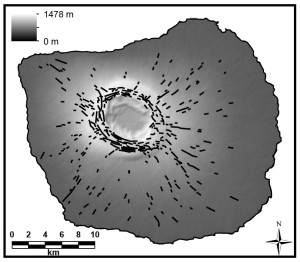

I am pleased to report that Shelley Chestler (’12) and I have just published her senior thesis research in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Using numerical finite element models, and targeting Fernandina volcano (shown at right) as a case study, the article demonstrates how minor, volcanologically plausible variations in a magma reservoir system can lead to the intrusion of radial, circumferential, and corkscrew-style dikes akin to those that characterize many volcanoes in the Galapagos and elsewhere. This result is an exciting one, offering a solution to a problem that has puzzled geologists for some time, and complementing other recent edifice-modeling efforts (e.g. Hurwitz et al. 2009; Galgana et al., 2012) we have now identified conditions that can lead directly to lateral intrusion of radial dikes from a shallow magma reservoir.

I am pleased to report that Shelley Chestler (’12) and I have just published her senior thesis research in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Using numerical finite element models, and targeting Fernandina volcano (shown at right) as a case study, the article demonstrates how minor, volcanologically plausible variations in a magma reservoir system can lead to the intrusion of radial, circumferential, and corkscrew-style dikes akin to those that characterize many volcanoes in the Galapagos and elsewhere. This result is an exciting one, offering a solution to a problem that has puzzled geologists for some time, and complementing other recent edifice-modeling efforts (e.g. Hurwitz et al. 2009; Galgana et al., 2012) we have now identified conditions that can lead directly to lateral intrusion of radial dikes from a shallow magma reservoir.