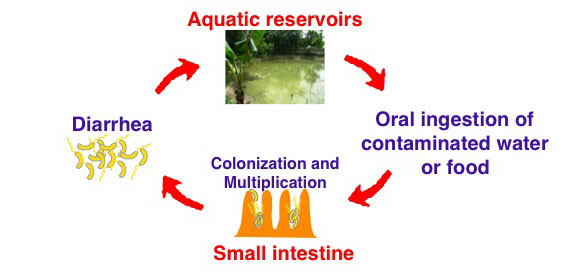

Each year 2-5 million people suffer from the diarrheal disease cholera. This disease is caused by V. cholerae, a mostly marine bacterium that also thrives in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract and in fresh water environments in cholera endemic areas. Upon ingestion by the host, V. cholerae colonizes the small intestine, multiplies extensively, and secretes cholera toxin. The toxin initiates a signal transduction cascade in the host that leads to a massive efflux of fluid into the intestinal lumen; this ultimately (in regions with poor sanitation systems) releases V. cholerae back into the environment. Thus, the life cycle of V. cholerae involves repetitive transitions between aquatic environments and the host GI tract (Figure 1). It remains unclear, however, how the bacteria are able to rapidly adapt to and multiply within these varying niches. Moreover, cholera represents a paradigm for complex, ecological bacterial diseases. Understanding the entire life cycle of V. cholerae, specifically how it modulates its physiology to adapt to different environments, is critical to enhancing our ability to combat infectious diseases as a whole.