Recently at the BFS I spotted a female Side-blotched Lizard (Uta stansburiana elegans) with a bright orange throat. “What’s up with that?” I asked, and the answer revealed a fascinating story of color polymorphisms and evolution of reproductive strategies in the Side-blotched Lizard.

The female Side-blotched Lizard (Uta stansburiana elegans) with bright orange nuptial coloration. ©Nancy Hamlett.

The bright orange on this lizard is a “nuptial color”, that is, a color that develops only during the breeding season, and it turns out that more is known about nuptial color in side-blotched lizards than in any other lizard on the planet!

The color patterns associated with reproduction in Side-blotched Lizards, however, are quite complex. During the breeding season, female Side-blotched Lizards can display either orange throats or yellow throats. Barry Sinervo’s lab at UC Santa Cruz has shown that the yellow vs. orange color is genetically determined by three alleles (o, b, or y) at a single locus, where orange (o) is dominant to the other two alleles, so that females with oo, bo, or yo genotypes develop orange throats, but females with genotypoes yy, by, or bb develop yellow throats.

A female Side-blotched Lizard with an orange throat at the BFS. The bulged abdomen shows that this female is gravid. (If this blog were a tabloid, we'd call it a baby bump.) ©Nancy Hamlett.

The Sinervo lab also found that the two different female color morphs have different reproductive strategies. Orange-throated females are r strategists; they produce many small eggs. In contrast, yellow-throated females are K strategists, which produce fewer but larger eggs. You might expect that over time one of these strategies would win out, but both persist because the relative advantage is density-dependent. When population density is low the orange-throated females, which produce more eggs, are favored, but as population density increases, larger progeny produced by the yellow-throated females have an advantage. The resulting dynamic causes population density to oscillate with a two-year frequency, and both strategies are maintained in the population.

Male Side-blotched Lizards also display throat color variations, and the colors are controlled by the same gene as in females. The genotypes, however, are manifested somewhat differently in males. The dominance relationship is o > y >b, so that are oo, bo, and yo are orange as in females, but only yy and by males develop yellow throats. The bb males develop dark blue throats.

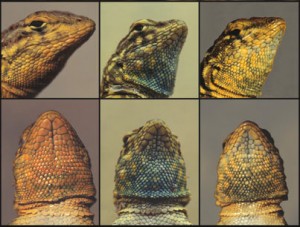

The three color morphs of male Side-blotched Lizards. From left to right: orange, blue, and yellow. ©Barry Sinervo, used with permission.

The three male color morphs also have different reproductive strategies. Orange-throated males have high testosterone, are aggressive, and control large harems of females. Blue-throated males are mostly monogamous and guard their mates, and yellow-throated males (which somewhat mimic females) are sneaky. They do not defend a territory, but sneak into other males’ territories to mate with females.

Evolutionarily, these three strategies play out like the game ‘Rock-Paper-Scissors’. Orange super-males best the mate-guarding blue males, and the mate-guarding blues best the sneaky yellows, but the sneaky yellows best the oranges. Each morph can steal mates from another morph (and thus increase fitness) when it is rare, but as each morph becomes common, it becomes more susceptible to losing mates to another morph. Thus no single morph should an win out, and modeling predicted oscillations in morph frequencies over time, which is what Sinervo’s lab observed in a 6-year study.

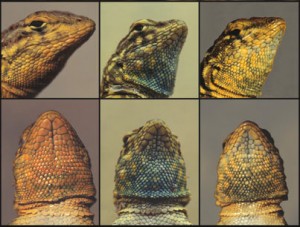

An interesting question is whether the Side-blotched Lizard population at the BFS behaves in the same way. The topology of the BFS, which is quite flat, contrasts with the rocky outcrops of the Sinervo lab’s study site, and since Side-blotched Lizards are not found in the suburban setting that surrounds the BFS, the population is genetically and demographically isolated. A search through our admittedly limited photo archive shows that the BFS appears to have both yellow and orange-throated males, with yellow appearing to be more common.

A male Side-blotched Lizard with an orange throat at the BFS. ©Nancy Hamlett.

A male Side-blotched Lizard with a yellow throat at the BFS. ©Nancy Hamlett.

It’s not clear whether blue-throated males are also present on the BFS; the photo below shows the bluest throat in the photos in our archive. Blues could well be there and just not detected in the small sample of photos. If blues are actually not present, then either a different dynamic occurs at the BFS or we would expect the oranges to win out over time. Whatever the case, this is clearly a great area for an enterprising student to investigate!

The male Side-blotched Lizard with the bluest throat in our BFS photo archive, but it’s not entirely clear whether it’s blue, yellow, or a blue/yellow hybrid. ©Tad Beckman.

Many thanks to Steve Adolph, Pete Zani, and Barry Sinervo for answering my many questions about Side-blotched Lizards!

References and further reading:

- Sinervo, B., & C.M. Lively (1996) The rock-paper-scissors game and the evolution of alternative male strategies. Nature 380: 240–243.

- Sinervo, B., E. Svensson, & T. Comendant (2000) Density cycles and an offspring quantity and quality game driven by natural selection. Nature 406: 985–988.

- Lancaster, L.T., A.G. McAdam, & B. Sinervo (2010) Maternal adjustment of egg size organizes alternative escape behaviors, promoting adaptive phenotypic integration. Evolution 64: 1607–1621.

Tags: Side-blotched Lizard, Uta stansburiana