Although I normally write a news post for any new additions to the BFS Biota Lists, your busy arthropod researchers – primarily Hartmut Wisch, Harsi Parker, and Jonathan Wright – have gotten ahead of me! Since March we have documented nearly 100 new taxa for the BFS Invertebrate List and added many new photos. Over the coming weeks, we’ll be adding posts that feature some of these new additions, but in the meantime, please peruse the list and the linked photos and enjoy this little Dr. Seuss-inspired sample:

From there to here, from here to there,

Funny things are everywhere

Some are old…

This pollen wasp, Pseudomasaris coquilletti (shown on on Phacelia distans), had been on our list, but the photograph is new. ©2010 Hartmut Wisch.

And some are new…

This snakefly, Agulla sp., not only represents a new genus, but a whole new order added to our list. ©2010 Harsi Parker.

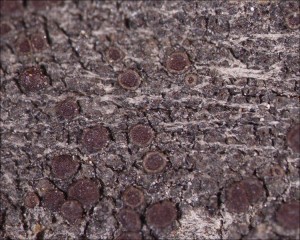

Some are red…

A Six-spotted Orbweaver, Araniella displicata, on Toyon (Heteromeles arbuitfolia). © 2010 Harsi Parker.

And some are blue…

Not one of them is like the other…

A female Digger Bee, Anthophora pacifica. The little holes you may have noticed in the island in pHake Lake are their nests. ©2010 Hartmut Wisch.

A little male Mellitid Bee, Hesperapis sp., sleeping in a Blue Dicks (Dichelostemma capitatum) on a cool, cloudy day. ©2010 Hartmut Wisch.

We don’t know why, go ask your mother!

Or better yet, please peruse our list and the informational links.

Tags: bees, insects, invertebrates, spiders